Jack Borok (’25) spent most of his young life in Los Angeles, unaware that the populous California city was also home to the modern descendants of the Gabrielino, Chumash and Tata tribes that occupied the basin when settlers arrived in the 18th century. He hadn’t learned that history until he came to UW–Madison in 2021 and took a class from Stephen Kantrowitz, the Linda and Stanley Sher Professor of History. Borok also learned about the lost village of Encino, a more than 3,000-year-old Gabrielino settlement that archaeologists had discovered … right across the street from the office building where his father worked.

Borok’s personal connection — and his research into its history — are at the heart of “Homeland, Hometown: Native and Settler Places,” a course Kantrowitz teaches to students in alternating years. The idea for the course sprang from one Kantrowitz formerly taught, “Native Madison After Removal.” He describes that class as an attempt to better understand the place he’s called home for the last 30 years. But it also raised several broader questions.

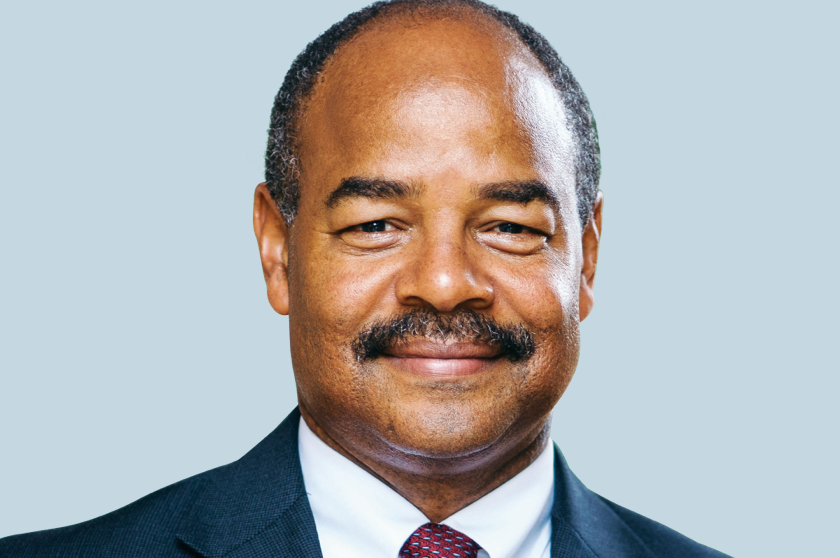

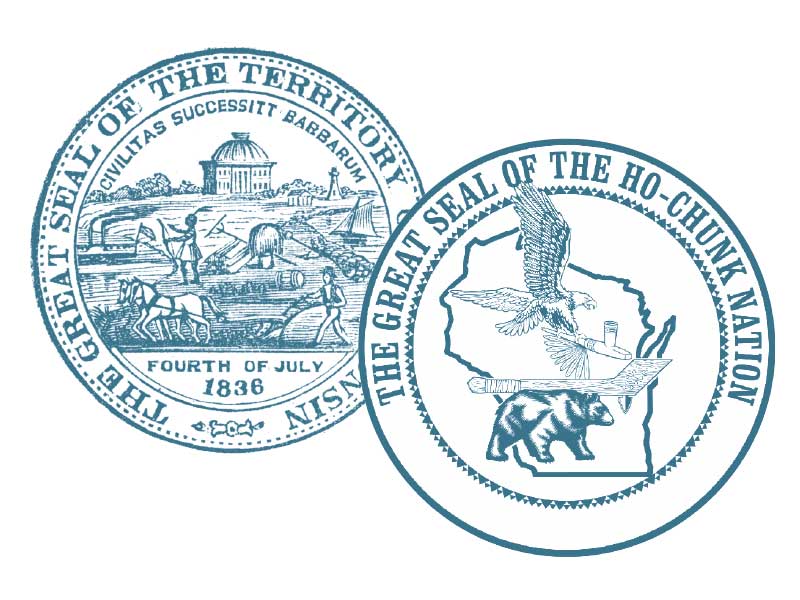

“I had the same insight that millions of non-Native Americans have had,” says Kantrowitz, whose 2023 book, Citizens of a Stolen Land, chronicles the experiences of the Ho-Chunk Nation in Wisconsin. “The light bulb goes off and you think to yourself, ‘Every square foot of this land used to be somebody else’s — until pretty recently, and for a very long time. And how come I’ve never thought of that?’”

That’s the central point of Kantrowitz’s hometown course, which asks students to research and report on the connections between their own hometown — a place they’re already deeply aware of and invested in — and Native American history.

Native people tend to disappear from the American history curriculum.

Most of Kantrowitz’s students have only a glancing awareness of this history when they come into his classroom, sometimes even the ones who grew up near Native communities in the Upper Midwest. Students from New York City, for instance, might not know much more than the popular, mythic story of Manhattan Island being bought for $24.

“Native people tend to disappear from the American history curriculum once it moves past the early 19th century,” says Kantrowitz. “Native people didn’t disappear from the United States, but they disappear from the curriculum by the Dawes Act in the 1880s, if not long before, and they very rarely make anything more than a cameo appearance in histories of the American 20th century or 21st century.”

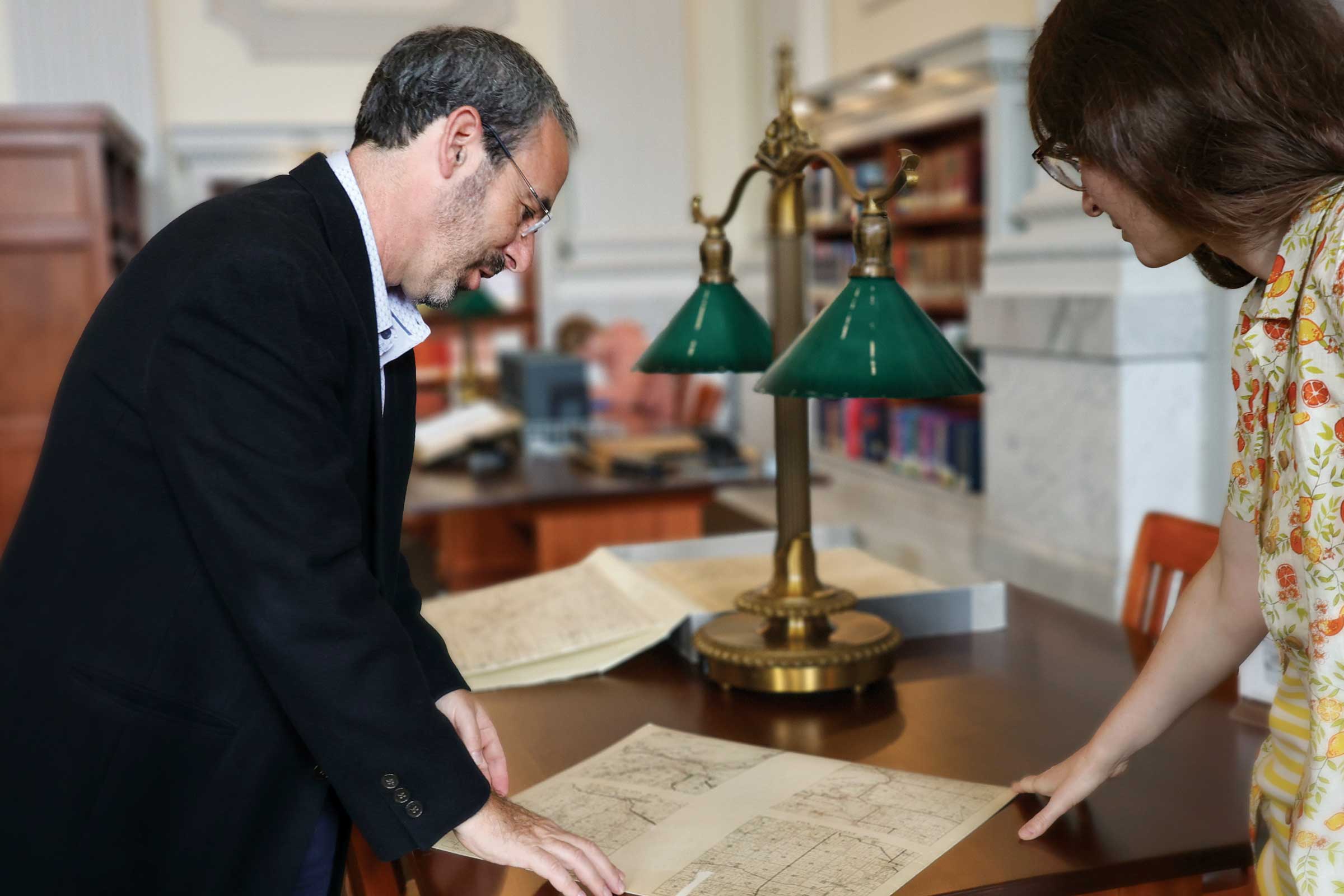

The first weeks of the class are organized around developing a kind of basic shared vocabulary of concepts, ideas, histories and approaches to historical research. Kantrowitz brings the students to the fourth floor of the Wisconsin Historical Society, where they get their hands on actual historical documents — personal letters, pamphlets, etc. — and their heads around the concept of archival research. Then they begin digging into the Native stories of their own hometowns.

Silas Cleveland, Jr. (’25), a Ho-Chunk student from the Black River Falls area who majored in history, didn’t take Kantrowitz’s hometown class, but he did take several others with him, including a class on Ho-Chunk history, and worked with him on a senior thesis. The senior thesis he researched to complete his degree would have perfectly fit the hometown syllabus. Cleveland uncovered that his ancestral tribe had been deeply involved in creating the thriving cranberry industry in nearby Central Wisconsin, which went into overdrive in the 1860s after a lumber boom (known colloquially as “The Cut”) took down most of the trees in the area. For Cleveland, learning the story cast a new light on his own history. Two of his brothers had worked for local cranberry farms.

“Reading history books, especially about my own people, is how the hometown thing comes in,” says Cleveland, who hopes to become a tribal lawyer. “When you’re learning about yourself, it feels like you’re learning more about your identity.”

In researching his own hometown connection, Borok learned about the U.S. conquest of California in the 18th century. But he also learned about the political complexities that area tribes are facing in contemporary Los Angeles. Many of them have struggled to regain federal recognition and have fought bitterly over sites each has claimed as their homeland. In that sense, Borok’s personal project tied neatly into one of the central concepts Kantrowitz hopes his students grasp: tribal sovereignty and the treaty relationships that currently exist between the United States and some (but not all) of the Native American tribes.

“My students all have to come into an awareness of Native people, not as isolated individuals, not as vanishing, not as subjects of plight or deprivation, but as communities of people enmeshed in a complicated history and a complicated relationship to non-Native communities in the United States,” says Kantrowitz. “For a lot of the students, those are the kinds of stories that they end up telling in this class.”

Kantrowitz likes to think of history as a glass plate holograph that’s been smashed into a million pieces on the floor. Each piece contains the entire image — but from a particular angle and at a resolution dependent on the fragment’s size. The hometown stories his students rediscover are like shards of Native American history.

“The smaller the story gets, the harder it is to resolve the whole larger story from it,” he says. “But the stories are in there, if you’re creative enough about how you approach it and think about it.”