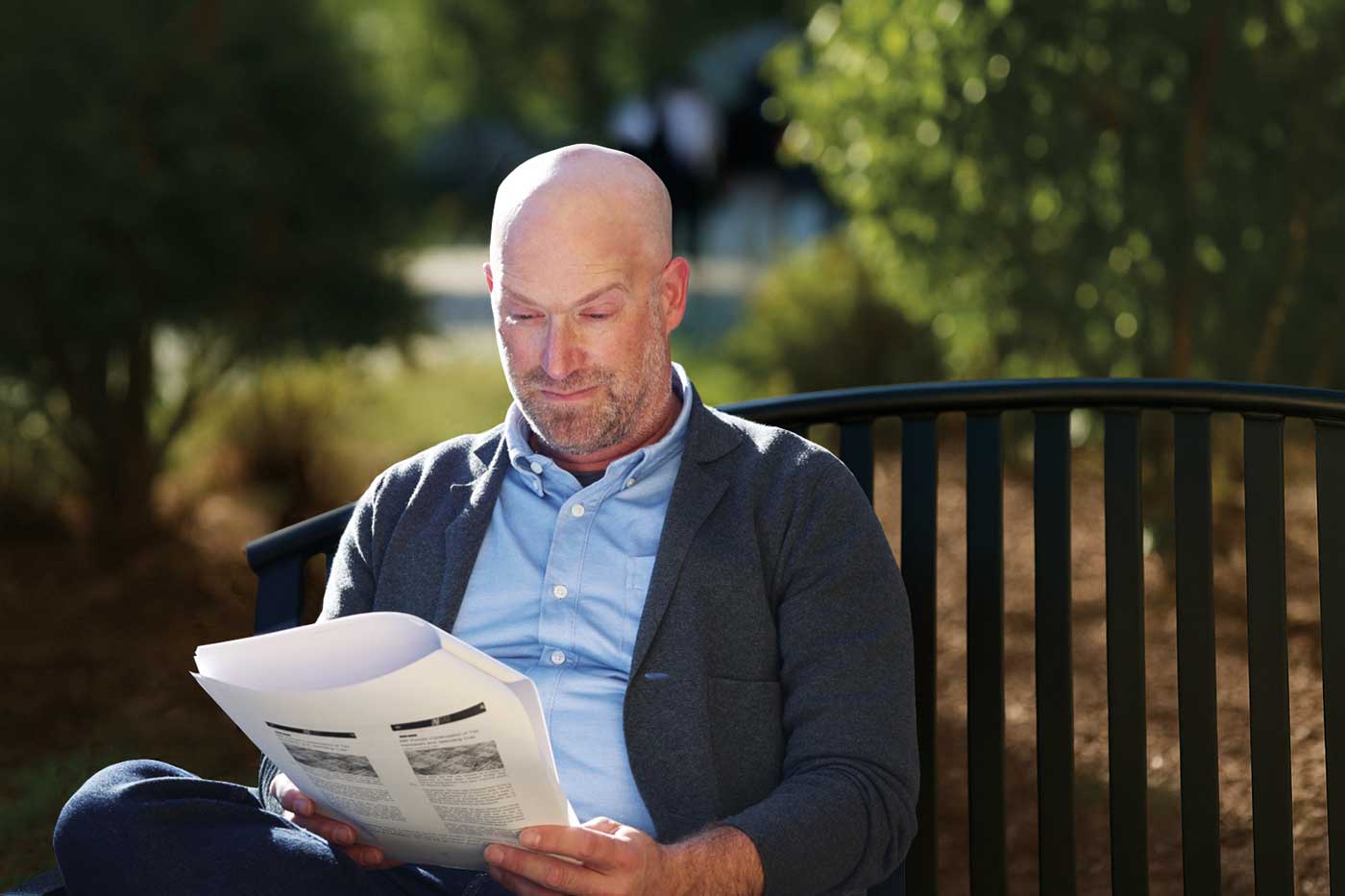

Earlier in his academic career, Mark Copelovitch would occasionally get into the kind of casual conversations you have with people in airports. When strangers would ask him what he did for a living, he’d reply, “I’m a political scientist.” Typically, the response would be something along the lines of, “Oh, it must be so interesting right now.”

That was back in the mid-2000s. The definition of “interesting” now has a whole new connotation.

“I study international political economy, international relations and European politics,” says Copelovitch, a professor of political science and in the La Follette School of Public Affairs. “My interests are at the intersection of all those things, which means that, right now, there are 97 crises going on.”

It’s not quite 99 problems, but it’s close. Since the beginning of 2025 alone, Copelovitch’s growing list of problematic developments has included the changing U.S. tariff strategy, a trade war with Europe, the question of whether NATO will continue to arm Ukraine, questions about cryptocurrency and debates around decisions of the U.S. Federal Reserve. All of these issues directly affect the global economy and the role of the U.S. dollar as the dominant currency, and all of them create a troubling amount of uncertainty in international politics.

“This is the fundamental thing we as international relations scholars talk about to our students,” says Copelovitch. “Bad things happen in world politics when there’s uncertainty. Whether you’re talking about war and security policy, nuclear weapons, international trade, money and finance, or environmental policy, mitigating uncertainty is the main goal. And now, we’re the chaos agent.”

Current events have raised plenty of concerns about the health of U.S. democracy and its political institutions. But unlike some of his international colleagues, Copelovitch finds he’s less concerned about the United States embracing isolationism and losing its power on the global stage.

“We’re in this paradoxical position where American democracy is deeply under threat at home and America’s commitment abroad to our closest allies and international cooperation is in serious doubt. And yet, because of the dollar’s entrenched dominance in global finance and the world economy, we are still more powerful than any other country in the world,” he says.

According to Copelovitch, international money and finance are a clearer indicator of global power than military might or population or GDP or other metrics, and about 70% of the global economy — trade, investment and financial transactions — runs on dollars. That fact means that other major global actors, like China and the European Union, aren’t really in position to unseat the United States as top dog. Both have their own sets of political challenges, many of which make America’s democracy concerns pale in comparison. And both would have to take drastic measures, including completely reversing many of their current economic policies, privatizing their banks and/or growing their financial markets to levels comparable to the United States, in order for their currencies to replace the dollar as the dominant international currency. All of that seems highly unlikely in either the next few years or even the remainder of the 21st century, says Copelovitch.

People have been predicting the end of American hegemony since Richard Nixon took us off of gold in 1971. And it keeps not happening.

“As bad as things seem right now, it’s like we’re the least ugly contestant in the global beauty contest for power in world politics,” he quips.

Current political upheavals and dramatic shifts in U.S. economic policies may seem more severe in the moment than at other points in recent history. But from Copelovitch’s perspective, the United States has been in an era of deep economic and political uncertainty since the financial crisis of 2008, and yet the U.S. dollar has remained the world’s reserve currency through all of it.

“People have been predicting the end of American hegemony since Richard Nixon took us off of gold in 1971,” says Copelovitch. “And it keeps not happening. As scholars, it should puzzle us that so many people have predicted something for the last 50 years, yet it keeps not happening.”

Copelovitch reminds his students that it’s important to hold two thoughts in their heads at the same time: The United States can be facing very serious domestic political challenges, even as it retains enormous structural power advantages in the international system especially given the country’s global financial dominance. As Americans, sometimes it’s difficult to see that other countries’ problems are at least as serious as America’s and that short-term domestic political developments do not mean the basic foundations of world order have completely changed. That’s a perspective he tries to convey to the students in his international relations classes, most of whom don’t have the same experience or long view.

“Our students’ entire adult awareness of the world is of a world in constant economic and political crisis,” he notes. “The post–Cold War era of optimism and stability, and the early 2000s when the economy was running along, and everybody thought everything was fantastic and stable — they don’t have any sense of that stability.”

It isn’t easy teaching students about how international organizations like the World Trade Organization or NATO work, or about how states sign and comply with trade agreements and other international treaties, in a world where many of those things are not currently working as they traditionally have. But Copelovitch believes it’s still critical for them to understand why the United States led the creation of those international institutions in the first place, and why they have made the world safer and more prosperous over the last 80 years.

“I’m somebody who is motivated by empirical puzzles,” says Copelovitch. “There’s real-world stuff happening, and we want to try and explain it — to try and understand what exactly happened that got us here. Because then maybe we can be better about thinking about what happens going forward.”