The Summer of Flooding

When the raindrops first began to fall in Central Texas early on the morning of the Fourth of July, nobody suspected that a mere three hours later, nearly seven inches of torrential downpour would swell the waters of the nearby Guadalupe River into a devastating flood that would tragically decimate a summer camp, wash out several communities and claim the lives of 135 people.

But events like the floods that devastated Kerr County are no longer unusual. This year alone, major flooding events have impacted areas in Kentucky, New Mexico and New Jersey. Not even Wisconsin and the Midwest have been immune: In August, flash flooding caused by storms in the greater Milwaukee area destroyed 51 homes, causing more than $76 million in damage. Scientists have dubbed 2025 “The Summer of Flooding.”

Andrea Dutton is surprised by exactly none of this. The Helen Jupnik Endowed Research Professor of Geoscience has spent her entire research career studying the historical connection between melting ice sheets and rising sea levels, with the aim of predicting how the latter is likely to play out in a world impacted by warming temperatures and climate change. She’s one of the world’s preeminent experts on the topic and also one of the most persistent voices warning communities — both on the ocean coasts and in the Midwest — about the flooding dangers posed by rising water levels.

“Communities need to know what’s going to happen, and that won’t be just sea level rise,” says Dutton. “Higher temperatures hold more moisture in the atmosphere. So, when it rains, you’re getting more intense rainfall, and you’ll have that superimposed on sea level rise, and you’ll have more intense hurricanes superimposed on top of that.”

What Dutton is discussing is a concept known as compound flooding, and it’s recently become a new focus of her research. Backed by a UW–Madison 2025 Research Forward grant, she’s collaborating with faculty in the College of Engineering and the College of Agriculture & Life Sciences to better constrain ice sheet disintegration and explore what compound flooding might look like in the future. Within that same grant, she’s also partnering with science communicators across campus to develop surveys so that she can listen to the people who will be impacted and understand their needs.

“We can’t walk into communities as scientists and say, ‘OK, this is what you need to do, and you just need to accept it,’” says Dutton. “That’s not going to work.”

The surveys will look at learning what is most important to people who live in flood-prone regions, with the aim of better designing science objectives and providing meaningful results to them. Dutton likens it to a patient visiting a doctor and being told they have heart disease and could be dead within the next five years: Do they continue their risky lifestyle, or do they take dramatic action to effect change? By getting communities that haven’t already been affected by flooding to think about what it could mean for their lives, she’s hoping communities won’t wait to do what cities in states like Louisiana and New York did only after devastation struck — creating berms and flood barriers and implementing green infrastructure to mitigate urban flooding.

It’s all about, how does it impact humans? How does it impact the people we care about? The more people who see that and get that message, the more inclined they’ll be to act on it.

“Is it that they can’t drive their cars down the street one day a year because of sea water flooding the road?” she asks. “Or is it five days a year? Maybe they can tolerate that. Well, what if it’s five days in a row? What’s their tipping point?”

Dutton keenly understands that it’s difficult for the public, most of whom have plenty of short-term concerns to distract them from what seems like very slow-moving problems like climate change. After all, she’s been sounding the alarm on it for decades now. But ignoring it risks eventually crossing a tipping point at which sea level rise and flooding threaten health and stability. Dutton points out that residents in a state like Wisconsin might not find themselves directly impacted by flooding caused by a hurricane in Texas, but the ripple effects could reach them. If flooding were to collapse the coastal housing market, it could have a profound impact on the national economy. And, potentially, more.

“If people can’t live in a place anymore, they’re going to have to retreat somewhere — and Wisconsin is probably going to become very popular,” she says. “We’re going to have problems just within our own country, about where people can live safely, and that habitable safe space is shrinking very rapidly.”

The issue isn’t likely to improve on its own. In a study released earlier this year, Dutton and several research colleagues argued that the 1.5-degree Celsius warming limit adopted by the Paris Climate Agreement — an agreement the United States has opted out of — is too high, and that such levels of warming are likely to cause polar ice sheets to melt at a rate that could cause sea levels to rise by several meters in the coming centuries. That’s the kind of increase that could erode coastlines, submerge the Florida Keys and cause even more serious flooding in coastal communities.

Dutton thinks about a picture that hangs on her office wall of a visit she made to an art exhibit in Florida that featured images of people standing in water in the places where they live. The photographer took a photo of Dutton standing in front of the framed images, using a glass prism to make it appear as though Dutton was standing in water as well.

“To me, seeing the people in the water is much more impactful than just seeing pictures of buildings with water,” she says. “It’s all about, how does it impact humans? How does it impact the people we care about? The more people who see that and get that message, the more inclined they’ll be to act on it.”

In the Neighborhood

Max Besbris didn’t see himself as somebody who studied environmental flooding, even though disasters and the environment are both key parts of sociology, his chosen academic field. But that changed in 2017 when Besbris, the H.I. Romnes Associate Professor of Sociology, was living in Houston. He was studying the impact of Hurricane Harvey, the largest rain event in United States history, and he found an unexpected calling.

“As someone who studied neighborhoods and studied residential mobility, it occurred to me that as more intense rain events and more unpredictable flooding become more commonplace because of global warming, this might matter for residential mobility,” says Besbris. “This also might matter for neighborhood inequality, the things that I had been trained to study.”

So Besbris and a colleague from Rice University, where he was teaching at the time, decided to zero in on Friendswood, a middle-class professional neighborhood outside of Houston. About a third of the town suffered serious flooding in the wake of Harvey. Besbris spent two years tracking and interviewing affected residents about their experiences.

You literally had neighbors getting exponentially different amounts of money for their recovery after flooding basically the same amount.

The result of their work was a book called Soaking the Middle Class: Suburban Inequality and Recovering from Disaster, an ethnography that charted how financial factors and community ties often impacted a family’s ability to recover from a flooding event, even within a well-resourced community.

Not surprisingly, Besbris discovered that whether a homeowner had a flood insurance policy was a significant determining factor for repair and recovery. Those who did were able to receive payments of up to $350,000 for their homes and personal property; those without insurance could only apply to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) for direct aid, in an amount typically in the mid-to-low $30,000 range.

“You literally had neighbors getting exponentially different amounts of money for their recovery after flooding basically the same amount,” says Besbris. “And that was one thing that was really important in determining whether or not, two years after the flood, households were built back up.”

A family’s social ties were also critical to recovery. But they were also critical to something else: a family’s decision to stay and try to rebuild in an area at high risk for future flooding events. Many Friendswood residents whose homes were destroyed decided to stay.

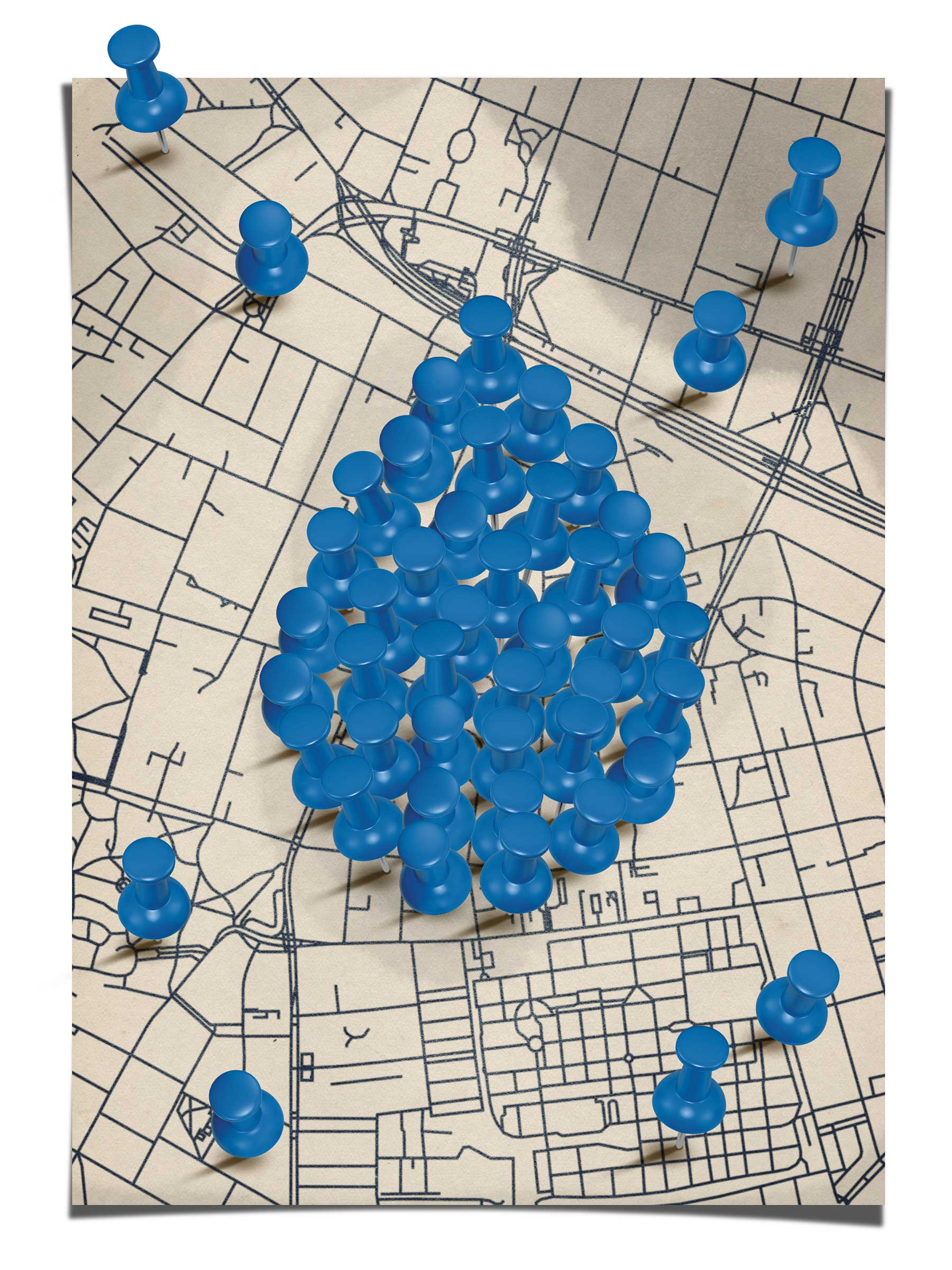

Building a Road Map

Turns out you can add “preparing for and recovering from floods” to the list of things that take a village.

Ed Boswell (PhD’18), a teaching faculty member in the Department of Planning and Landscape Architecture, teaches his students how to apply geographic information systems (GIS) and geodesign to a host of environmental issues, including helping communities across Wisconsin prepare for severe flooding events and other hazards. His students effectively become connectors that use the information these systems provide to unite a wide range of disparate groups to find workable solutions. This work happens through coursework and community-based learning through UW–Madison programs such as the UniverCity Alliance and the Rural Partnerships Institute.

“Geodesign is focused on tools for visualization, analysis and, importantly, stakeholder input to create planning and design scenarios,” says Boswell. “What’s cool is this process facilitates input from engineers who model flooding, community members who can tell us where flooding has occurred in the past and municipalities who put plans into action. My goal in teaching is to underscore the importance of bringing these disciplines into the process.”

Boswell’s students work primarily with ArcGIS, a comprehensive geospatial platform, to learn tools and processes to involve multiple stakeholders and ultimately help inform planning and design decisions.

In partnership with UW Sea Grant and Silvernail Studio for Geodesign, Boswell and his students linked ArcGIS online applications to a prototype digital sketching and tracking tool they’re calling ScenarioStudio. The tool enables design and planning teams together with stakeholders to design scenarios with green infrastructure or other landscape practices on the fly, then visualize and compare their potential impact in real time, all informed by existing spatial data.

In the early phase of planning and design, we can use these tools to visualize topography, soil data and other existing conditions to inform the placement of green infrastructure.

“Say, for instance, that we want to increase the amount of stormwater that can be absorbed in an area by incorporating green infrastructure and reducing the amount of impermeable surfaces,” says Boswell. “In the early phase of planning and design, we can use these tools to visualize topography, soil data and other existing conditions to inform the placement of green infrastructure.”

Critically, the tools include key performance indicators (KPIs), a measurement that indicates, for example, how much stormwater a particular strategy is likely to capture and how much it may cost to install and maintain. These data are displayed in real time through dashboards that are easy to interpret.

As part of a UniverCity Alliance UniverCity Year project, Boswell’s students have helped communities in the Koshkonong Creek watershed in Wisconsin respond to frequent flooding events and created an ArcGIS StoryMap to assist the City of Waupaca with communicating information on a potential dam removal project.

More than anything else, Boswell’s classroom strategy aims to take a big-picture approach to flood risk.

“These tools and approaches encourage us to think on a regional or watershed scale,” he says. “The water doesn’t care where municipalities end. We need to think on that scale and erase the boundaries.”