When we arrived at the emergency room, my five-year-old son was struggling to breathe. Doctors and nurses jumped into action with swabs, IV liquids and X-rays. Immediately, they administered nebulized racemic epinephrine (NRE), which is the first-line treatment for difficulty breathing. The NRE bought us time while we waited for test results, which revealed a severe strep infection, treatable with antibiotics. Despite the stress and fear that day, I was grateful for the medical professionals who knew what to do. But why did they know what to do? The answer involves more than a century of scientific advancement, not just in medicine but in all the related fields that led to NRE — the medication needed to open my son’s airways.

For thousands of years, people have known that naturally occurring compounds can help with difficulty breathing, like ephedrine produced by the plant Ephedra. George Oliver and Edward Schafer made a breakthrough in the 1890s when they demonstrated that adrenal gland extract could alter heart rate and blood pressure. Soon after, chemists set out to purify the compound responsible for this effect. Two labs (those of John Abel and of Jōkichi Takamine) succeeded almost simultaneously, and in 1901, Takamine and his technician Keizō Uenaka patented adrenaline, opening the door for future research. Initially, the drug was given as an injection, but in 1910 physiologists George Barger and Henry Dale proved that inhaling epinephrine is more immediately effective. This is when epinephrine became widely used as a bronchodilator — the same way it was used for my son.

The research didn’t stop there. By the 1940s, teams of physicians were carrying out large clinical studies comparing the effects of racemic epinephrine to other formulations. Cardiologist James Alexander and pulmonologist Maurice Segal confirmed that when delivered through a nebulizer, the racemic mixture was fast-acting and long-lasting with few side effects, making it the go-to treatment for adult patients with difficulty breathing. The use of NRE in children began in the Mountain West in the 1960s where, due to the thin air, children with difficulty breathing are at higher risk.

So, here’s my kid, 60 years later, coming into the ER with a constricted airway, and he is quickly met by a respiratory therapist who calmly administers NRE, confident it will help. And I can take a deep breath, too. We owe this confidence to generations of scientists who pushed the boundaries of knowledge, not knowing if their efforts would make a difference. Oliver and Schafer didn’t experiment with adrenal extracts to save my son but because they thought the world should know what adrenal glands do. Because of them, Takamine was driven to find and patent the active compound, in turn allowing researchers at universities across the country to test its effectiveness. And behind all these advances are societies that value and invest in science of all kinds.

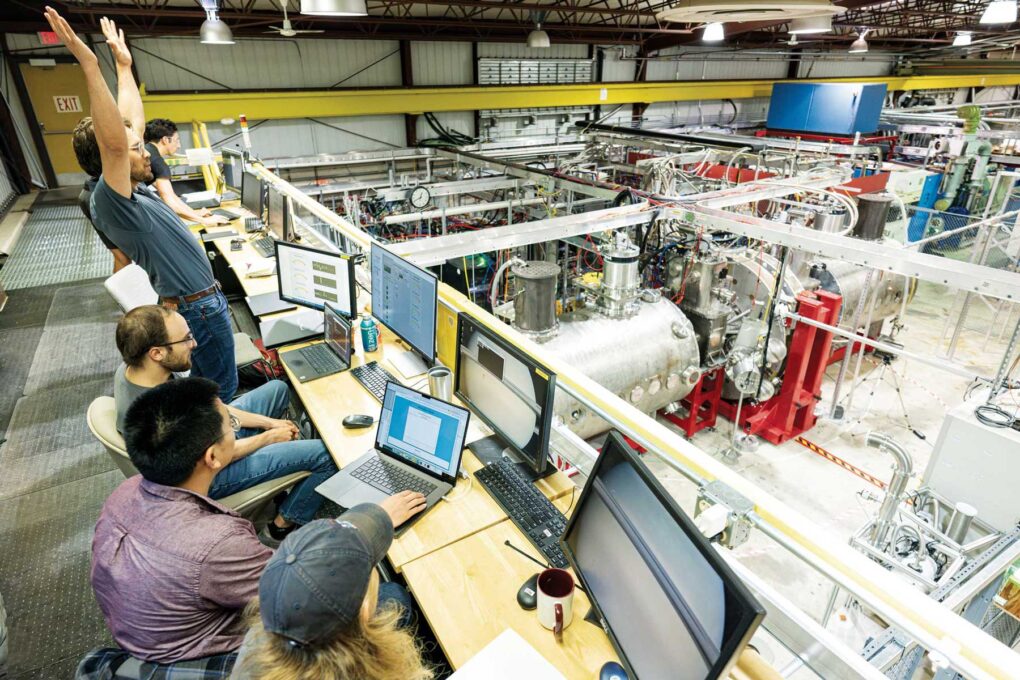

As a researcher myself, I’m scared that science as we have known it is coming to a screeching halt. Decades of investment in basic research, including in the people and places where science happens in our country, are being defunded by the federal government with complete disregard for the consequences. This is not the future I want for my kids. I want to tell them that they can go to a university where students are free to learn about anything and can do it alongside scholars who’ve dedicated their lives to learning. I want to tell them that people are working hard on cures for cancer and that one day we are going to get there. For that to happen, more people must understand that basic science matters. I hope that’s you.