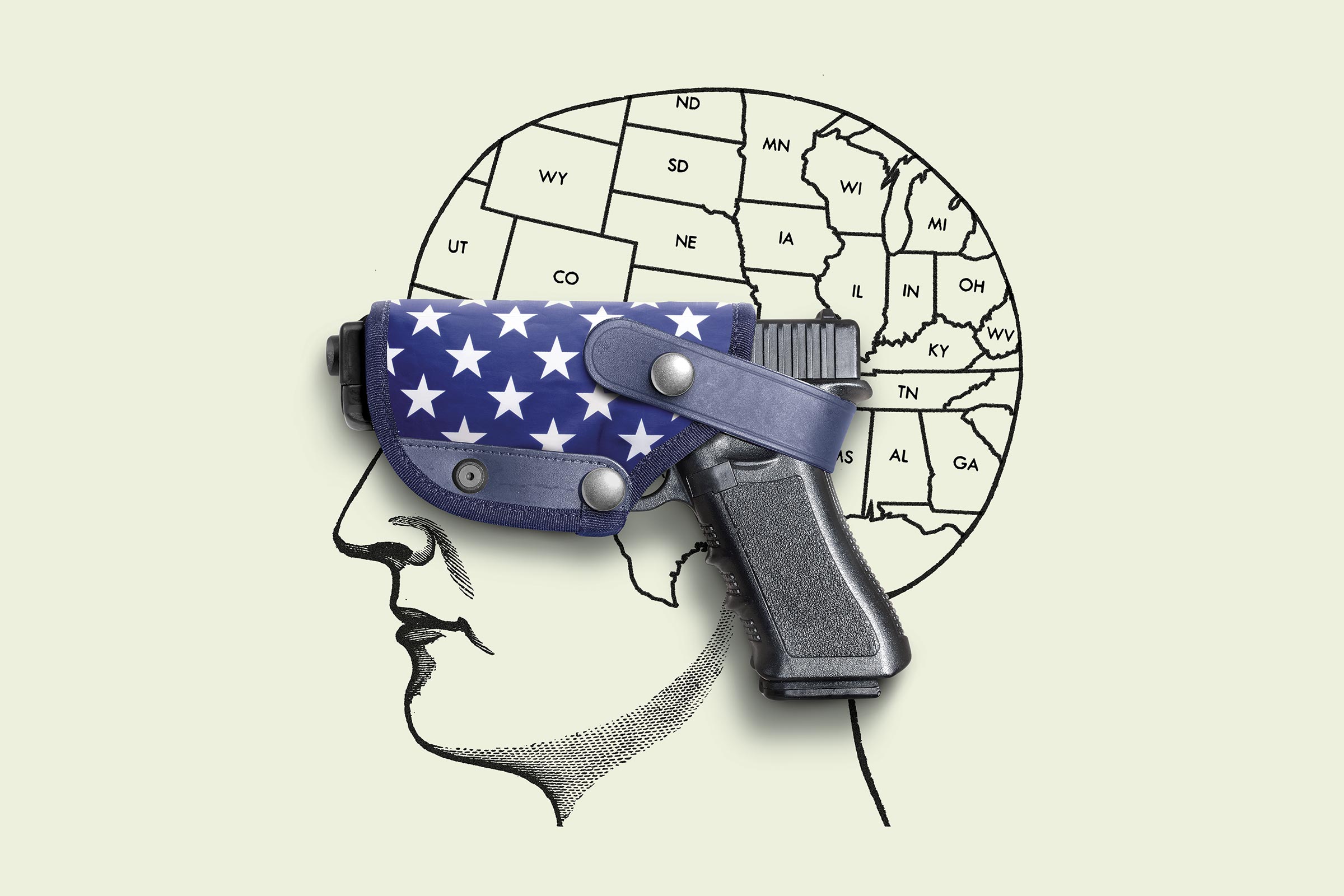

Consider the following: According to the Pew Research Group, 40 percent of Americans live in a house with a gun, and 30 percent of Americans own one.

There are 393 million civilian-owned guns in the United States, a number large enough that every single individual could have one, with several thousand left to spare.

“The fact that we have all these weapons around—nowhere else in the world looks anything like us,” says Nick Buttrick, an assistant professor of psychology. “And you have to explain that somehow. You can’t understand what it means to have an American psychology without grappling with that as a core feature.”

Buttrick has made it his mission to examine the psychology of gun ownership in America, a problematic and politically fraught topic to say the least. But in a country in which a six-year-old in Virginia brought a gun to class and shot his teacher—and it’s not even the most shocking gun-related incident to occur in 2023—the pursuit seems not just interesting, but essential.

“We’re very good at telling stories about why the things that we’re doing are right, normal and just,” says Buttrick. “And the fact that the United States has been the only place that has this level of gun ownership implies that there are a lot of people with this incredibly dangerous object in their lives, and they’re still able to tell themselves the same story that everyone tells themselves: that their lives are right, just, good, not unusual and safe.”

Buttrick grew up in New York, a part of the country that didn’t sport a particularly strong gun culture—an origin story that has occasionally made the interviews he’s conducted with gun owners and members of gun clubs challenging. As a social psychologist, Buttrick is fascinated by the ways in which individuals construct worldviews to help them navigate their daily lives. Psychologists argue that an individual’s three most fundamental needs are feeling safe, feeling in control and belonging to meaningful communities. For many Americans, gun ownership checks all three.

Studying this issue in Wisconsin, one of the states that maintains a deep and active hunting culture, has provided an interesting contrast for his research.

The fact that we have all these weapons around – nowhere else in the world looks anything like us. And you have to explain that somehow.

“Being able to look at the older American style of gun ownership built around hunting and sport—as opposed to this newer style of ownership—which is much more about protection from evil, being able to sort of disentangle that is a really fascinating aspect that I’m looking to push my research toward,” Buttrick says.

Buttrick’s most recent research project suggested that America’s deep obsession with gun ownership may have crystallized in the post–Civil War era, when former slaveowners began using them to protect their way of life. Buttrick found that counties with the highest levels of enslavement in the late 1860s are also the ones with the highest levels of gun ownership today and are the ones where guns and protection are most tightly linked.

Buttrick also finds himself particularly fascinated with the circular psychology that seems to underpin gun ownership. In order for a gun to feel useful, he argues, an individual has to believe two things: that the world is dangerous, and that society is unwilling or unable to offer protection. But once you have a gun, individuals exhibit a tendency to see the world as a more dangerous place—and, as the political discourse of the last few decades has shown, it also leads to sharp arguments over whether the government or interest groups might try to take it away or regulate it.

“If you think this is the only thing that’s keeping you safe, the only thing that’s keeping control, the only thing that’s keeping you valued, well, of course, you don’t want to give it up,” says Buttrick. “Finding ways of exploring that tension is one place where some of this work can be meaningful.”

And there’s another. With horrific mass shootings in America remaining a routine part of news headlines—including a recent attack that took place on the Michigan State University campus, taking the lives of three undergraduate students—Buttrick and his lab have also turned their attention to the impact of such shootings on local communities.

“How do people respond to these sorts of tragedies?” he asks. “Is it different from other sorts of tragedies that take people away, like car accidents? That’s something we need to explore.”