To tackle the biggest questions, it helps to have a big team.

And there aren’t many questions more massive than the ones related to the origins of life on Earth and whether other worlds—the ones we already know and the ones we have yet to discover—could someday support life.

“This is one of humanity’s biggest existential questions: Are we alone in the universe?” states Richard Townsend, chair of the Department of Astronomy. “Even if the only other thing in the universe is single-celled organisms or some weird sort of crystalline silicon life, it doesn’t matter. It’s a complete philosophical game changer.”

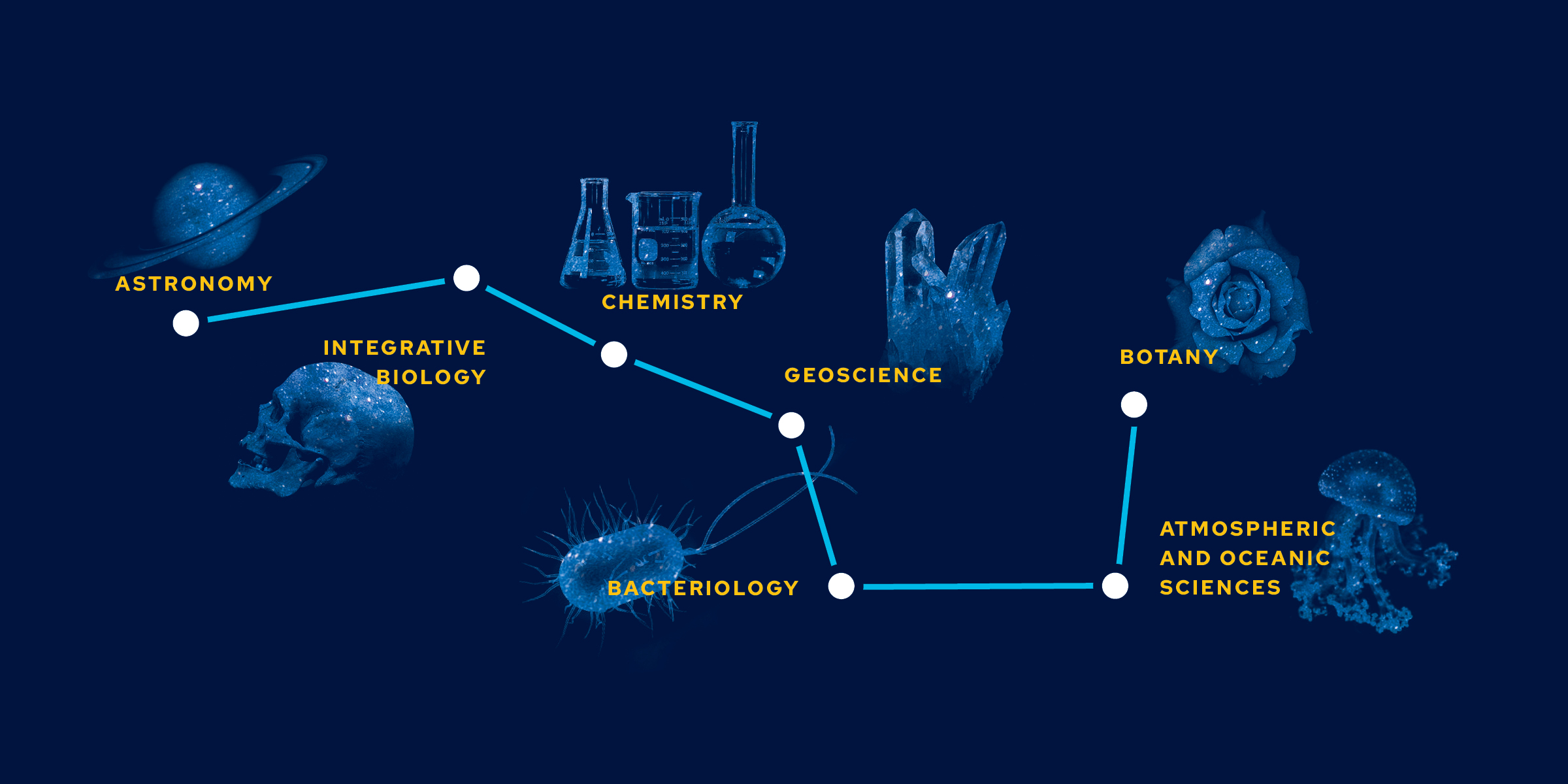

The group Townsend is currently assembling could be a complete game changer, too. The Wisconsin Center for Origins Research (WiCOR) is a new multidisciplinary group that includes researchers from a whopping seven departments: astronomy, chemistry, integrative biology, geoscience, bacteriology (in the College of Agricultural & Life Sciences), botany, and atmospheric and oceanic sciences. Its creation is philanthropically supported and funded in part by the Department of Astronomy’s Board of Visitors.

“The study of life’s origin on Earth and potential origin elsewhere in the universe is catching fire now, thanks to new theories, novel experimental approaches, and the excitement of upcoming solar system exploration,” says David Baum, a professor of botany who studies the evolution of living organisms. “UW has great strength in this area, but until now we have not been well coordinated.”

WiCOR found its own spark of life in Origins, a 2019 multimedia project that UW-Madison Communications produced on the connections between research in the departments of astronomy, geoscience and anthropology. When Sebastian Heinz became chair of the Department of Astronomy that same year, he set out to build on that collaboration, using WiCOR as a vehicle. Then the recruiting began in earnest.

The Power of Connection

Like a constellation of connected stars, the Wisconsin Center for Origins Research (WiCOR) will unite researchers from a set of seven academic departments, several of which haven’t typically collaborated before. Some don’t even use the same terminology to describe certain common phenomena: Mathematicians characterize the links between the Earth and ocean tides using the term “tidal Love coefficients,” named for the researcher Augustus Love, while astronomers call them “overlap integrals.” Learning each other’s academic languages is just one of the benefits WiCOR is likely to confer. “We all have something to contribute to this field,” says astrochemist Susanna Widicus Weaver.

Susanna Widicus Weaver, an astrochemist whose appointment is split between chemistry and astronomy, was recruited to Madison in 2020. Shortly thereafter, a more expansive origins of life cluster of faculty positions was approved, resulting in three new assistant professors flocking to UW-Madison. Betül Kaçar, a professor of bacteriology, is an astrobiologist who studies ancient DNA. Thomas Beatty, a professor of astronomy, studies signs of life on exoplanets. Zoe Todd, a professor whose appointment, like Widicus Weaver’s, is split between chemistry and astronomy, studies early Earth chemistry and the delivery of biomolecules via impacts from comets and meteorites.

The recruitment process and creation of WiCOR has linked faculty colleagues who weren’t aware each other’s research was going on, let alone interrelated to their own.

Already, new synergies are starting to pop. Widicus Weaver studies how chemistry evolves in the formation of stars and planets. Kaçar and Todd study how planets and the life that might be on them form from the mix of material that Widicus Weaver identifies. And Beatty can take those findings to determine whether an exoplanet could support life or not.

[WiCOR] opens new ways of thinking about the science and new paths to creativity in science. And that’s exciting.

“We know that there are more than 5,000 exoplanets orbiting other stars,” says Townsend, who studies the properties of massive stars. “We’re at the point where we can start measuring the composition of their atmospheres. We’re starting to talk to people in atmospheric and oceanic sciences, and they will be talking to people in geoscience who, in turn, will be talking to people who figure out how microbes can weather rocks and change the atmospheric chemistry.”

WiCOR will be located on the sixth floor of Sterling Hall in a space that’s being reimagined to promote a spirit of collaboration, with conference rooms and open areas for faculty and graduate students.

“We don’t want something that’s going to be a bolt-hole where people can hide from their departments,” quips Townsend. “We want something where people will bump into other people and interact with them.”

WiCOR will clearly be many things to different people, as evidenced by the metaphors each scientist uses to describe it. To Widicus Weaver, it’s an umbrella that covers a diverse and interdisciplinary field.

“It opens new ways of thinking about the science and new paths to creativity in science. And that’s exciting,” she says.

To Baum, it’s the center of a pie, where the tip of each departmental slice touches key scientific questions about the origins of life. Townsend selects a different term to describe WiCOR—a bridge.

“We were very careful to space people at a regular distance along the bridge so that, although somebody at this end of the bridge might not understand somebody at the other end of the bridge, they will always have a neighbor to talk to who could talk to the next person,” he explains. “And slowly we can get to a point where we can all talk to each other.”

To students, WiCOR could be a clearinghouse that puts them on the cutting edge of the biggest questions in origins of life research.

“We will offer experiences that will give students skill sets that they can’t develop anywhere else,” says Widicus Weaver. And maybe, just maybe, answer some of the universe’s biggest questions.